Each year, a Cape Cod ham radio club commemorates the role that wireless communication played in rescuing survivors from the Titanic in 1912.

The Club calls itself the Titanic/Marconi Association of Cape Cod. Their call sign is WIMGY, the last 3 letters of which were the same call sign of the Titanic.

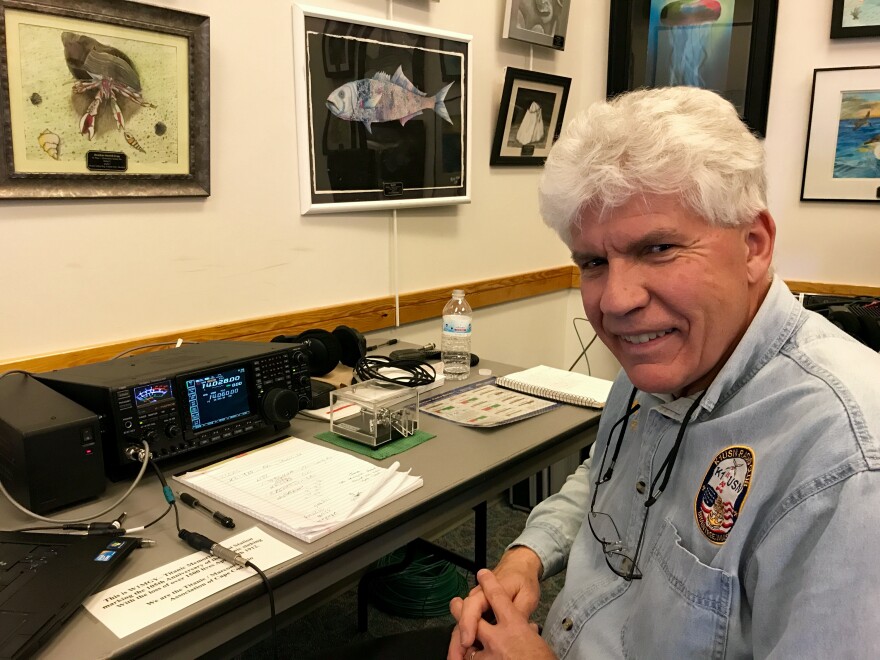

Rick Pendleton hails from Braintree, but he comes to the Cape every year to participate in the event.

“We’re trying to re-create the historic transmissions that took place between the Titanic and the coastal stations,” said Pendleton. “And it’s a commemoration of Marconi’s technology that was a very important part of the rescue operation.”

Pendleton taps out Morse code in a room at the National Seashore’s Salt Pond Visitor Center in Eastham. (The Seashore partners with the club to put on the annual event.) His transmitter is state of the art – a far cry from 1903, when Guglielmo Marconi built a station in nearby Wellfleet to experiment with sending radio signals over the airwaves. By 1912, passenger liners like the Titanic were outfitted with wireless setups. The emerging technology offered the only way to send and receive messages once at sea, but its limitations also contributed to the great loss of life when the ship went down.

Park Ranger Barbara Dugan helps the club stage its yearly event. She says that on the night of the disaster, another ship – the Californian – was in the area, but their wireless operator had gone to bed by the time the Titanic struck an iceberg.

“And even though the flares from the Titanic were seen, the ship’s crew on the Californian thought the Titanic was just sending off flares for a party,” Dugan said.

Another ship, the Carpathia, was 67 miles away. The wireless operator on board contacted the Titanic to let them know the Marconi wireless station on Cape Cod had been sending them messages all day.

The crew on the Californian thought the Titanic was just sending off flares for a party.

“The Titanic operators weren’t copying because their radio actually broke down,” Dugan said. “Then they get it fixed, and they’re backed up with messages because the Marconi company makes money by sending private messages for people on board the ships. They feel rushed to get that job done, so they’re not listening for new messages.”

Eventually, the Titanic’s wireless operator received the Carpathia’s message.

“Their reply was: ‘Help us…we’re sinking,’” said Dugan.

The Carpathia immediately sailed toward the stricken ship, arriving 3-1/2 hours later, and saving 705 of its passengers.

The Titanic’s captain was faulted for not properly heeding iceberg warnings, but poor wireless communication was also found to have played a role in the disaster. As a result, Congress passed the Radio Act of 1912 which, among other things, established the SOS international distress signal.

Rick Pendleton continues to keep the Titanic story alive using the dots and dashes of old-fashioned Morse code. He said he hears from ham radio operators around the U-S, and from such far-flung places as Cuba, Poland, the Ukraine, Germany and Russia.

“What you get is, ‘Thank you for the special event,’” Pendleton said. “You hear that a lot, because people are thrilled to get a contact with an activity that’s related to something very unusual and historic. They like to be able to communicate with someone that’s trying to keep the legacy of Marconi alive.”