This is Part 1 of a 3-part series on increasing vehicle traffic on the Steamship Authority ferries to Nantucket and Martha’s Vineyard and how the communities it impacts are responding.

Let’s start with a simple question: Who runs the Steamship Authority? Currently, it’s a five-member board of governors, with representatives from Nantucket, Martha’s Vineyard, Falmouth, Barnstable and New Bedford. But it hasn’t always been that way.

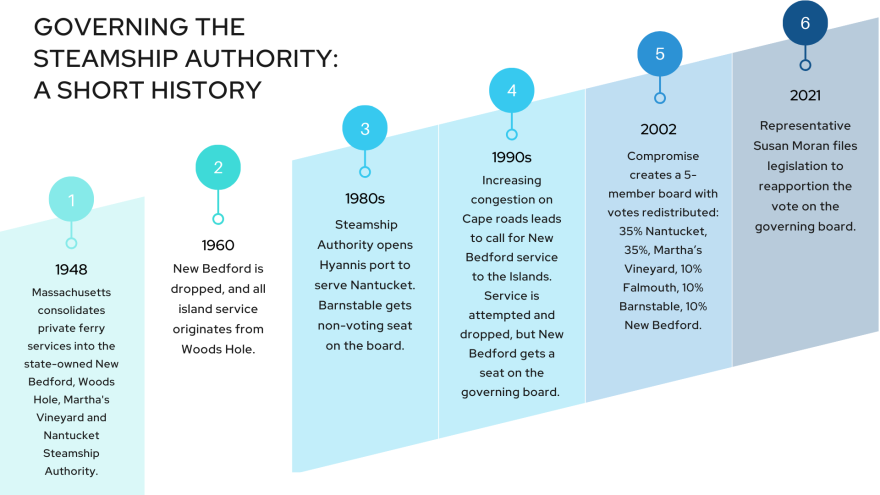

In 1948, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts consolidated what were private ferry services into the state-owned New Bedford, Woods Hole, Martha's Vineyard and Nantucket Steamship Authority, with most service originating in New Bedford. But as it was plagued by big deficits and poor service, island officials appealed to the Massachusetts legislature to restructure the boat line, which it did in 1960.

"New Bedford" was dropped from the company's name then, as all service for both islands began originating in Woods Hole.

Former state rep Tom Cahir says the 1960 Steamship board had three members representing Falmouth, Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket. Not only was the vote equally divided among the three, but to ensure some fiscal discipline any budget deficit was to be shared equally as well.

But other than a couple of years in the beginning when there was a small deficit, the Steamship Authority has operated deficit-free for 60 years. And the islands, with a combined two thirds majority vote, had control over Authority decisions.

But because all passenger and freight traffic to both Islands went through Woods Hole, congestion in that Falmouth village soon became a serious problem.

With Increasing Traffic Demands, Authority Looks to Barnstable

Former Authority employee Scott Peterson remembers it was one particular policy that brought the issue to a head in the 1970's. “The straw that broke the camel's back for Falmouth was when Steamship was offering guaranteed standby,” said Peterson. “There’d be cars stacked up from Woods Hole almost up to the traffic lights at Quissett in the summertime—there’d be 100, 150 cars stacked up. It was just madness.”

As the situation worsened in Falmouth, the Authority looked to Hyannis as a port which could provide faster service to Nantucket and relieve some of the traffic from Woods Hole. But the town of Barnstable was wary of getting involved with the Authority, its representative Bob Jones said.

The town of Barnstable did not welcome the Steamship in with open arms. They didn’t want it.Bob Jones, Barnstable's representative to the SSA

“The town of Barnstable did not welcome the Steamship in with open arms,” Jones said. “They didn't want it. They knew the history: prior to 1960 they were having deficits continually. The Town of Barnstable wanted nothing to do with that.”

But there was nothing Barnstable could do to stop the authority since, by law, it had the power to buy and develop what land it needed, where it needed, for a terminal.

To seal the deal, Jones remembers, Barnstable was told it didn’t have to pay any part of a deficit and was given a non-voting seat on the Board of Governors and with that service began in the late 80s.

“It started out just passengers, just summer,” Jones said. “And then after a couple of years, the Authority said they needed to start running freight out of here. Eventually it came to them saying, ‘Well, we need to run freight out of here year-round.’”

But as Steamship Authority activity increased, the traffic congestion became worse in Hyannis, just as it had in Woods Hole.

That’s when efforts were made to get New Bedford involved and a commission was formed to study the problem, former state rep Cahir recalled.

The 'New Bedford Wars'

The Cass commission was formed, “back in the early 90s, talking about the importance of getting New Bedford in the mix so maybe we could divert some of that traffic off of Woods Hole Road and get people over from New Bedford,” said Cahir.

And New Bedford was interested as well. Julie Wells, the editor of the Vineyard Gazette, explained why New Bedford wanted back in. “There were powerful political interests on Beacon Hill, and I think that they saw the Vineyard as key to New Bedford's revitalization,” said Wells. “They were revitalizing the historic areas in downtown New Bedford. They wanted tourists.”

And New Bedford officials wanted Barnstable to join them suggesting they could absorb some of the Nantucket-bound traffic that was clogging the streets in Hyannis.

That lead to what has been called "the New Bedford wars," when the city used its powerful political allies on Beacon Hill to make a change in the Steamship Authority's governance structure.

“It was also a lesson in what can happen when you go to the state legislature,” Wells said. “It was really wild, they were doing everything in the back room. And the next thing you knew, you had this legislation that had been filed to completely overhaul the Steamship Authority and change the power structure.”

The Islands, fearing they might lose their majority control over the Authority, rallied against the effort. Nantucketers arranged for busloads of islanders to descend on Beacon Hill with buttons saying, "Don't Rock the Boat."

For the Islanders, it had the desired effect, Wells said. A compromise was reached in 2002: although Barnstable and New Bedford were added to the board, the islands maintained their majority, each with 35% of the vote. The remaining 30% was divided among Falmouth, New Bedford and Barnstable, and it has been that way for the past 20 years.