Michael Burghardt couldn't sleep. His legs were shaking, his bones ached and he couldn't stop throwing up.

Burghardt was in the Valley Street Jail in Manchester, N.H. This was his 11th stay at the jail in the last 12 years. There had been charges for driving without a license, and arguments where the police were called. This time, Burghardt was in after an arrest for transporting drugs in a motor vehicle.

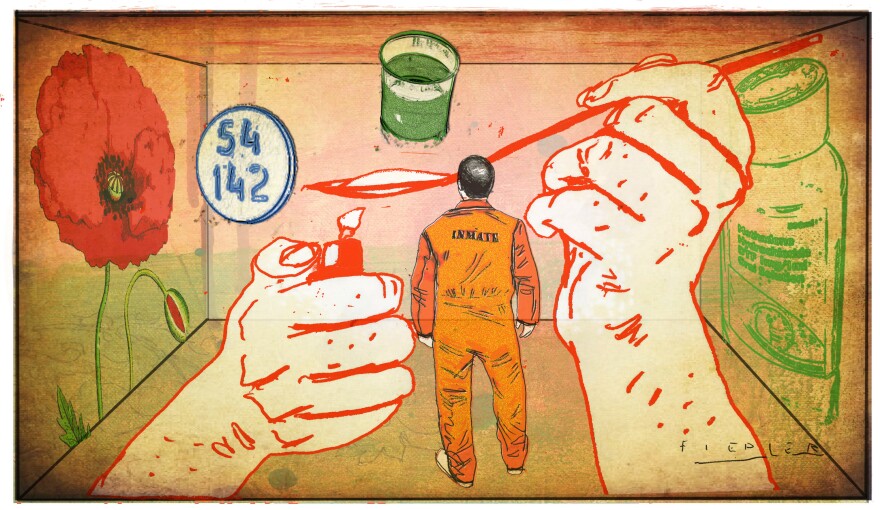

Burghardt, 32, has been taking methadone for 10 years to help his recovery from heroin addiction. Each time he's been in the jail, he says, he hasn't been able to continue with the medication-assisted treatment. He hasn't been able to taper off the medicine either, which means he's had to go straight into detox.

Four times after he was released from jail, Burghardt says, he relapsed and started using heroin again.

Methadone is a long-acting narcotic that can help people stay off heroin. But the physical symptoms of withdrawal from methadone can last longer than those from the drug it replaces. "You feel like you're basically dying," Burghardt says.

The World Health Organization recommends that incarcerated people like Burghardt continue methadone treatment. And if Burghardt lived in most other Western nations – or Iran, Malaysia or Kyrgyzstan for that matter — he likely would be able to do so.

But in the United States, the only people likely to receive methadone or other opioid- replacement drugs, such as buprenorphine, while incarcerated are pregnant women.

That's the case at the Valley Street Jail. "It's for the safety and health of the child more than anything," says Denise Ryan, the jail's administrator for health services. Withdrawal from opioids can cause miscarriage.

According to a survey published in the journal Drug and Alcohol Dependence, more than half of the nation's prison systems offer methadone to people behind bars. But most restrict access to pregnant women and, occasionally, those with chronic pain.

Far fewer jails and prisons provide patients with buprenorphine, another opioid replacement drug. Drugs like methadone and buprenorphine are "summarily stopped when people are incarcerated," says Dr. Josiah Rich, a professor of medicine at Brown University and co-director of the Center for Prisoner Health and Human Rights. "That's the prevailing practice," but, he says, it's one that should change.

Although involuntary opioid withdrawal isn't directly fatal for adult drug users, it can be "indirectly fatal," says Dr. Heidi Ginter, assistant chief medical officer for Community Substance Abuse Centers, a chain of treatment centers in New England. As inmates detox from methadone, their tolerance for opioids goes down while their cravings go up. That sets them up for an overdose after they're released, says Ginter. She says a third of her clients spent time behind bars before they sought treatment.

Burghardt knows how it feels. "You're dying for a fix," he says. Scheduling an appointment at a methadone clinic, however, takes days or even weeks. "So you end up relapsing and using again," he says. Burghardt says this cycle took the lives of three of his friends recently.

In fact, research shows incarcerated drug users are as many as eight times more likely to die immediately after release than at other times in their lives. And, patients who terminate methadone treatment are eight to nine times more likely to die immediately thereafter than those who don't.

Sometimes, Ginter says, clients end up behind bars while in her care. After undergoing prolonged and painful detox from methadone while incarcerated, she says, many choose heroin over treatment after they get out. "I'm basically having a conversation with somebody where they're opting for the lesser of two evils," she says. "That feels really hard."

Ginter's experience isn't unique. In one study, inmates who received methadone behind bars were eight times more likely to seek treatment and stay off drugs during the month following their release than those who received only counseling. In another study, drug users who were not incarcerated were also more likely to seek out methadone treatment when they knew they could continue it behind bars: an indication of how inevitable incarceration can feel for people addicted to illegal substances.

Still, corrections administrators say they prefer abstinence-based treatment programs. They worry that methadone, even when administered as a liquid, can be retained in inmates' mouths then sold and abused behind bars. Jails and prisons in New Hampshire already face smuggling of Suboxone, a variety of buprenorphine that is manufactured as a papery film, making it easy to conceal in books and mail.

There are practical concerns. Although methadone is inexpensive, facilities would either have to become licensed to administer it or transport patients to methadone clinics, as many do for pregnant women.

Ginter says for her, those reasons don't cut it. "This is a human rights issue," she says. "If somebody with diabetes eats a piece of cake at a birthday party, they don't get incarcerated. And their doctor doesn't say, 'Now I'm not going to prescribe your insulin because you ate a piece of cake.' "

Copyright 2021 New Hampshire Public Radio. To see more, visit . 9(MDA1MzU5NTYzMDEyNzY2MjYxMzZjODE4NQ004))