Solar and wind are our energy future, but these most modern innovations actually harken back centuries.

Witness Cape Cod’s saltworks industry.

The Brits were hoping to make salt here soon after the Pilgrims arrived in 1620, but lack of a clay base to hold evaporating water meant they had to boil down small batches in kettles and then scrape the sides. Not until 1776 did John Sears, known as “Sleepy John” and later “Salt John,” set out to create solar-powered saltworks, shallow vats fed by Cape Cod Bay at Quivet Neck (then the northside of Yarmouth, now Dennis).

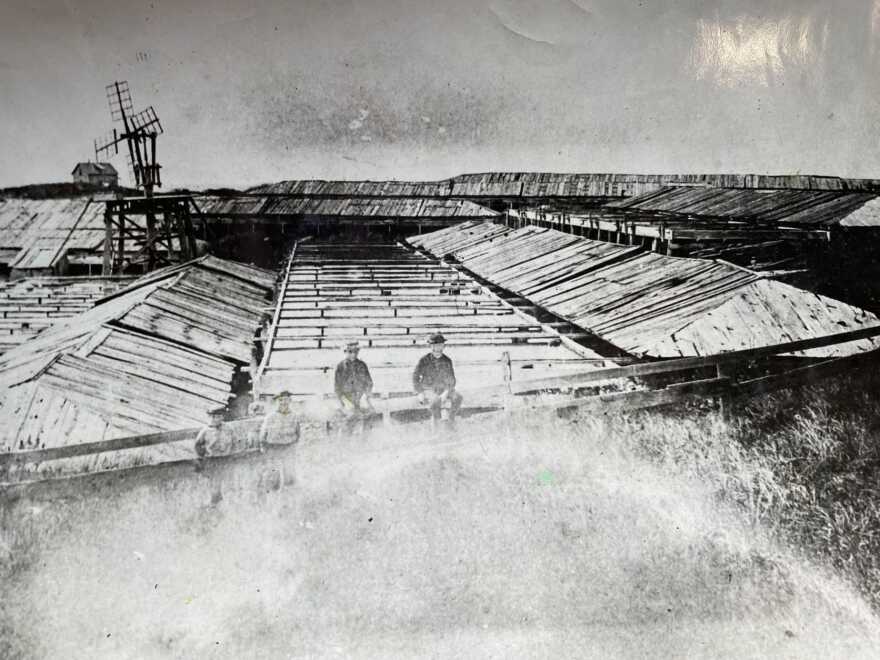

His first efforts weren’t successful, partly because of leaks. So he caulked and then scavenged a bilge pump off the famous Outer Cape wreck of the British warship Somerset to move more water. Wooden coverings to protect vats from rain, pulled aside in sun, created a checkerboard look. There were three stages during weeks of evaporation. 350 gallons eventually made one bushel of salt, 80 pounds.

Salt was the crucial preservative for the essential fishing industry. One of many vessels plying to the West Indies used 700 bushel a year packing fish into hogshead barrels. That’s a market, and production wasn’t expensive; free seawater, unattractive land easy to appropriate along the shore, technology solar passive (though windmills became an important power source for drawing up).

By 1802, according to Henry Kittredge’s history of “Cape Cod,” 136 salt makers had set up shop. By 1830, 442 Cape businesses made more than 500,000 bushel a year not counting secondary products like “Glauber” salt (apparently used to prevent hides from stiffening) and Epsom (still a soak for joint ailments).

During the 1820s and 1830s, Provincetown alone had 20 to 30 mills with circling arms wrapped in canvas, drawing water through hollowed logs into vats covering scores of lowland acres. This was the dominant shoreside industry, but by the 1840s production began to decline. Salt mines in upstate New York created competition. Protective tariffs fell away and that played a big role in the gradual demise.

A devastating storm in 1858 smashed mills and wrecked infrastructure, though salt preserved wood as well as fish; rock-hard planks were scavenged for homes that are still standing today. Some commercial production continued into the late 1880s, especially on the south side of Yarmouth near Bass River, managed by a deeply-rooted Quaker community.

This dynamic economic driver left few remnants save old photos, a few street names, some wallboards, and a replica at the Aptucxet Trading Post in Bourne – plus some boutique saltmakers for a high-end market, far from packing hundreds of thousands of pounds into fish barrels.

Yet the best words to describe an almost-forgotten, anachronistic industry are most modern:

Powered by wind. Using solar energy. Sustainable.

—

Read more of Seth Rolbein's work here on A Cape Cod Voice.