On a windswept, remote Truro dune sits a low-slung, nondescript cement block building surrounded by chain link fencing topped with barbed wire — no identifying sign, no indication of use or purpose. What once were windows are sealed with more cement block, walls painted neutral beige. A garage door is the only suggestion that large objects come and go.

“This used to be the telephone exchange station for the Air Force,” explained Cape Cod National Seashore Historian Bill Burke, back when this was a military base, a perimeter warning station against feared Ruskie attack.

Inside, the modern use becomes clear: This is a repository, storage created in 1996. It holds relics and artifacts the National Seashore has chosen to protect, only a small eclectic portion of what is offered year after year, a hodgepodge as old as 3500 years, as recent as this lifetime.

Coast Guard lifesaving, cranberry history, Marconi wireless, Native American artifacts, whaling captain mementos, antique furniture, a Narwahl whale tusk, a Nauset Marsh duck boat from the late 1800s.

A rocking chair plunked on a shelf belonged to the wife of Captain Edward Penniman, his preserved house in Eastham a Seashore destination. She accompanied him on whaling voyages, and had the rocker’s curved runners flattened so she could sit more stably, the seas taking care of the rocking.

Whalers hunted polar bears for meat and sport so there’s a white pelt.

A cabinet holds a collection of Native American blades, points and tools from what’s called the Coburn site in Orleans. These were fashioned around 3500 years ago. Burke said there are conversations about returning these artifacts to the Wampanoag Tribe, whereby all rights they belong.

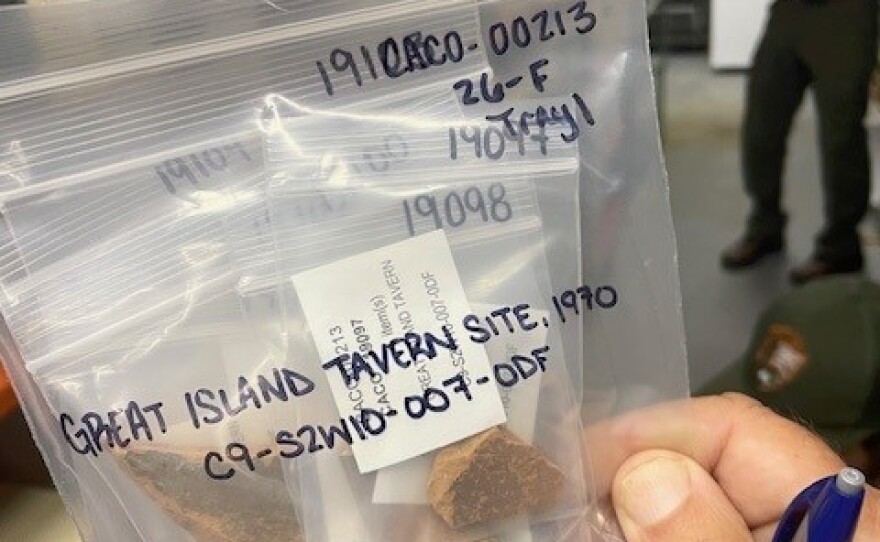

Rows of boxes hold 80,000 shards and chunks from a 1970 archeological dig at Smith Tavern on Great Island in Wellfleet, where people hung out in the 1700s. That sounds like a huge amount, but they’re mostly little chips of bowls, bottles, clay pipes, window (and drinking) glass, plaster, “not sexy stuff,” smiled Burke, though sometimes they fit together to create an evocative bowl.

Because the building is cement block, without much traffic, it keeps cool in summer but needs winter heat. Curators like it to be around 50 percent humidity, under 75 degrees. What they really hate are wild temperature swings. “So,” says Burke, “we’re in pretty good shape.”

Safekeeping is the goal, which can become the opposite of accessibility. That is a tension every curator faces, putting evocative and intimate objects in a dormant anonymous space, in boxes and under sheets, in cabinets and lining walls, inaccessible.

There is one whimsical relic I regret I didn’t get a chance to see or touch, protected in a secure box, the key not available at the moment: The pen John F. Kennedy put to paper, sitting in the White House in 1961, when he signed legislation creating the Cape Cod National Seashore.