PROVINCETOWN—Shortly after 9/11, Ada Limón visited Cape Cod for the first time.

She spent seven months here honing her poetry at the Fine Arts Work Center, and reveling in the town's nature and solitude. On Friday, 23 years since receiving that "beautiful gift of a fellowship," Limón is returning to Provincetown, this time as U.S. poet laureate.

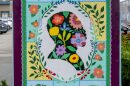

"You Are Here: Poetry in Parks," Limón's initiative with the National Park Service and the Poetry Society of America, will feature poetry installations honoring nature in parks across the country. During this week's event, Limón will read seven handpicked American poems, which will be installed on a picnic table at Cape Cod National Seashore.

Patrick Flanary Your connection to Provincetown dates to shortly after 9/11. Where were you on 9/11, and how did your experience shape your writing fellowship here soon after that?

Ada Limón, U.S. poet laureate I had been living in Brooklyn when 9/11 happened, but was in Los Angeles. I was on the very first flight that left L.A. for New York a few days later. I, of course, like many of us who were living in New York City and all across the world, was just completely overwhelmed and shattered. And at the same time, here I was going to go on this fellowship for the Fine Arts Work Center. And at the same time, we were going down and making hot food for all of the volunteers and the firemen helping onsite at Ground Zero. So going out to the fellowship was such a weird time, because how do you leave the city that you feel so bonded to after such an enormous, tragic event?

PF How were you able to leave?

AL I had this beautiful gift of a fellowship, and yet my heart was really anxious. And the benefit of the fellowship was that there were many of us who were coming from New York City. So we really bonded in that community of everyone really feeling that immense weight and the loss and the grief, and working through that together. And then it also reminded me that the writing, and writing through things, is a way of laying something down. It's the way of taking it off your chest and letting the page hold it for you.

PF "You Are Here: Poetry in Parks" is your national campaign to to feature American poems in seven national parks, and to celebrate the poetry-nature connection. These are not your poems. How were they chosen?

AL I really wanted to pick poems that everybody could relate to, that you didn't have to be a poet in order to understand and cherish. And so I chose poems that were by real icons of the literary world, but also poems that were openhearted enough, I think, to allow anyone who might be traveling to the parks to read and understand and inspire people to write their own.

PF This project is connected to your role as U.S. poet laureate. I'm wondering what other social responsibilities come with that title, if any.

AL I was asked to serve by the Librarian of Congress, Dr. Carla Hayden. My job is to really expand the audience for poetry. And I deeply believe that if we all read and wrote poetry and spent more time in a contemplative state addressing our feelings and our emotions, that we would be better off as a human species. For me, the calling was quite easy to accept because it is about the expansion of the audience.

PF One of your poems published about four years ago by The New Yorker is called "The End of Poetry." At 194 words, it is a single sentence long. How how do you make those decisions about punctuation, rhythm, tone?

AL One of the things about poetry that I love is that in order for it to exist in the world, it has to have a form so that when someone is receiving that form, they know how to read it. They know how to let those words enter their body. And so you have the line breaks and the punctuation, and you have all of these ideas of repetition. And in doing that, you're allowing that song of the poem to enter the reader. That poem in particular is a build. And so it builds slowly, slowly, slowly. And as it builds, it ramps up. You can hear that not only in the punctuation, but in the musicality of the syntax and all of the words that are swirling at the end, so that it builds into a really powerful wave that signals that here is the time for me to allow a different kind of emotion to take place in the body.

The event on Friday begins at 10 a.m. at the Beech Forest Trail in Provincetown. Ada Limón will unveil Mary Oliver's poem "Can You Imagine." The late Oliver lived in Provincetown for 50 years and served on the Work Center's committee.