When Greg Wetherbee and his colleagues started collecting rainwater in early 2017, microplastics were the last thing on their minds. What they were looking for was evidence of air pollution washing out in the rain. They found that, but they also found plastic - not just a piece or two, but fibers and shards in nine out of ten samples.

"These results are actually accidental and opportune,” said Wetherbee, who is a research chemist with the U.S. Geological Survey in Lakewood, Colorado.

Wetherbee and two collaborators collected rainwater from a range of urban and wilderness sites around Colorado, and filtered the water to collect small particles of air pollution. Before sending the filters off to a lab to be analyzed, Wetherbee decided to just take a look at them.

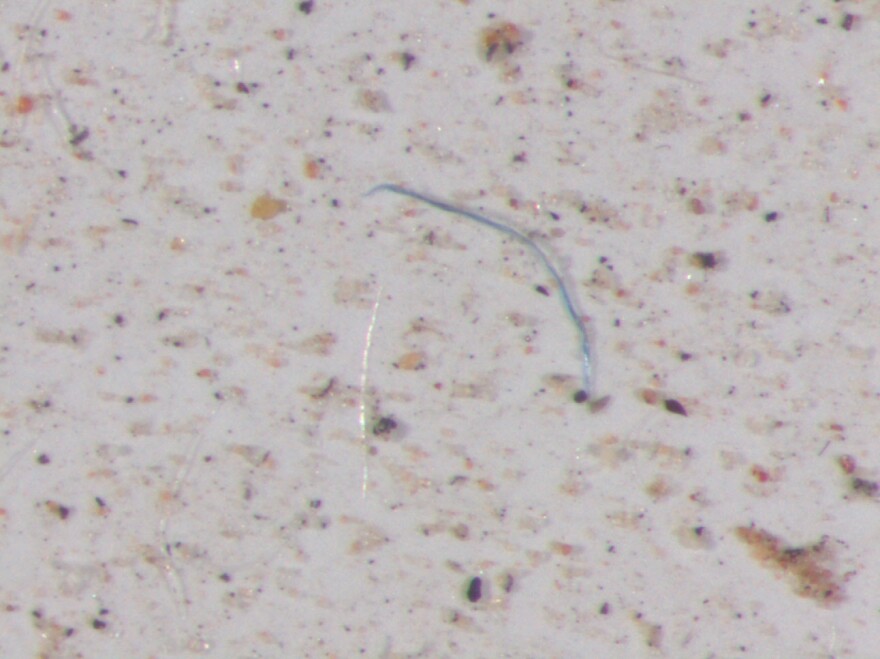

“When I did, I was pretty amazed at what I saw,” Wetherbee recalls. “I decided to take photographs of every filter under magnification, and I specifically targeted the plastic particles that I could identify.”

The most common type of plastic was fibers, and blue was the predominant color. But Wetherbee observed a rainbow of fibers, shards, and beads. They ranged in size from a few microns to a few millimeters, but none of the plastic was visible to the naked eye.

It's not clear how the plastic gets up into the sky, but Wetherbee says they suspect it is blown into the air. There was more plastic in rainfall collected in Boulder and Denver than in remote, mountainous areas, suggesting that it’s a local phenomenon.

As for where the plastic came from, that’s another open question. Wetherbee notes that blue fibers could come from any number of sources, including blue tarps and synthetic clothing.

Wetherbee says his isn’t the first study to find microplastics in rainwater. But there are currently more questions than answers about how much plastic is in rain, how widespread the phenomenon is, where the plastic comes from and how it gets into rain. Perhaps the most important questions is: what does this mean for the ecosystems where the plastic is falling?

“I don't know how these materials affect ecosystems. I don't think that the scientific community really knows, either,” Wetherbee said. But I think that we need to find out.”

While Wetherbee never expected to find – or study – microplastics, he says it’s now an important and growing part of his research.